… If [the Birth-Controller] can prevent his servants from having families, he need not support those families. Why the devil should he?

If anybody doubts that this is the very simple motive, let him test it by the very simple statements made by various Birth-Controllers like the Dean of St. Paul’s. They never do say that we suffer from a too bountiful supply of bankers or that cosmopolitan financiers must not have such large families. They do not say that the fashionable throng at Ascot wants thinning, or that it is desirable to decimate the people dining at the Ritz or the Savoy…

But the Birth-Controllers have not the smallest desire to control that jungle. It is much too dangerous a jungle to touch. It contains tigers. They never do talk about a danger from the comfortable classes. The Gloomy Dean is not gloomy about there being too many Dukes; and naturally not about there being too many Deans. He is not primarily annoyed with a politician for having a whole population of poor relations, though places and public salaries have to found for all relations. Political Economy means that everybody except politicians must be economical.

The Birth-Controller does not bother about all these things, for the perfectly simple reason that it is not such people that he wants to control. What he wants to control is the populace, and he practically says so. He always insists that a workman has no right to have so many children, or that a slum is perilous because it produces so many children. The question he dreads is “Why has not the workman a better wage? Why has not the slum family a better house?” His way of escaping from it is to suggest, not a larger house, but a smaller family. The landlord or the employer says in his hearty and handsome fashion: “You really cannot expect me to deprive myself of my money. But I will make a sacrifice. I will deprive myself of your children.”

— G. K. Chesterton, quoted from Gilbert Magazine, Volume 12 Number 8 (July/August 2009)

Archive for the 'G.K. Chesterton' Category

(More) Chesterton on Birth Control

Published August 15, 2009 Ethics , G.K. Chesterton , Marriage and Family , Politics Leave a CommentTags: Birth Control, G. K. Chesterton, Gilbert Magazine

The Uniqueness of Man

Published March 8, 2009 G.K. Chesterton , Philosophy 1 CommentTags: Darwin, evolution, G. K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy

I have no problem with the theory of evolution. God could have created our bodies in an evolutionary way as well as any other way. The existence of the soul united to our bodies is a totally different matter. However, if we focus on the biological, we have much in common with our primate friends; but this is saying much more than is often supposed. It is quite the logical leap to say that because man’s body has evolved from the animals, that he is also one of the animals. Man also has the ability to reason, and this is what primarily separates him from the beasts. G. K. Chesterton also noted that what separates man from beast is man’s penchant for dogma – “Man can be defined as an animal that makes dogmas.” There is so much that separates man from animal: the propensity to worship, the desire to paint chapel ceilings, the romantic instinct to compose poetry, the soaring spirit that composes symphonies, and so on. There is indeed a missing link, but as Chesterton also noted, “If there were a missing link in a real chain, it would not be a chain at all.” As I said, I have no problem with the theory of evolution, but the conclusions sometimes drawn from this theory suffer from an astonishing amount of fuzzy thinking. To think that man is only a beast requires a myopic focus on the biological, but what else are we to expect from a culture that puts such a shallow focus on the body. Chesterton paints the picture far better than I could, so I will get out of the way and let him speak.

I have no problem with the theory of evolution. God could have created our bodies in an evolutionary way as well as any other way. The existence of the soul united to our bodies is a totally different matter. However, if we focus on the biological, we have much in common with our primate friends; but this is saying much more than is often supposed. It is quite the logical leap to say that because man’s body has evolved from the animals, that he is also one of the animals. Man also has the ability to reason, and this is what primarily separates him from the beasts. G. K. Chesterton also noted that what separates man from beast is man’s penchant for dogma – “Man can be defined as an animal that makes dogmas.” There is so much that separates man from animal: the propensity to worship, the desire to paint chapel ceilings, the romantic instinct to compose poetry, the soaring spirit that composes symphonies, and so on. There is indeed a missing link, but as Chesterton also noted, “If there were a missing link in a real chain, it would not be a chain at all.” As I said, I have no problem with the theory of evolution, but the conclusions sometimes drawn from this theory suffer from an astonishing amount of fuzzy thinking. To think that man is only a beast requires a myopic focus on the biological, but what else are we to expect from a culture that puts such a shallow focus on the body. Chesterton paints the picture far better than I could, so I will get out of the way and let him speak.

From the final chapter of Orthodoxy (GKC Collected Works, Vol. 1, Ignatius, 1986):

If you leave off looking at books about beasts and men, if you begin to look at beasts and men then (if you have any humour or imagination, any sense of the frantic or the farcical) you will observe the startling thing is not how like man is to the brutes, but how unlike he is. It is the monstrous scale of his divergence that requires an explanation. That man and brute are like is, in a sense, a truism; but that being so like they should then be so insanely unlike, that is the shock and the enigma. That an ape has hands is far less interesting to the philosopher than the fact that having hands he does next to nothing with them; does not play knuckle-bones or the violin; does not carve marble or carve mutton. People talk of barbaric architecture and debased art. But elephants do not build colossal temples of ivory even in rococo style; camels do not paint even bad pictures, though equipped with the material of many camel’s-hair brushes. Certain modern dreamers say that ants and bees have a society superior to ours. They have, indeed, a civilization; but that very truth only reminds us that it is an inferior civilization. Who ever found an ant-hill decorated with the statues of celebrated ants? Who has seen a bee-hive carved with the images of gorgeous queens of old? No; the chasm between man and other creatures may have a natural explanation, but it is a chasm. We talk of wild animals; but man is the only wild animal. It is man that has broken out. All other animals are tame animals; following the rugged respectability of the tribe or type. All other animals are domestic animals; man alone is ever undomestic, either as a profligate or a monk. So that this first superficial reason for materialism is, if anything, a reason for its opposite; it is exactly where biology leaves off that all religion begins.

Universal Patriotism

Published February 28, 2009 G.K. Chesterton , Philosophy Leave a CommentTags: despair, G. K. Chesterton, hope, Orthodoxy, Suicide

G. K. Chesterton is uncomfortable with both pessimism and optimism in the way that they are commonly defined. This is not such a novel view since we all assume that there is a “middle way” between the despair of the pessimist and the naivete of the optimist. Chesterton’s real insight is that the real problem with both the optimist and the pessimist is that each comments on the universe as a critic, as one looking over a piece of art in a gallery. A critic is one who, supposedly, critiques something from the outside as a “impartial observer”; but such an idea is ludicrous when critiquing the cosmos. We cannot stand outside of the universe and judge it impartially, for we are a very part of this universe. There is no outside of all that is.

Chesterton says that his attitude towards the cosmos is not something akin to pessimism or optimism, but rather patriotism. In Orthodoxy (GKC Collected Works Vol. 1, Ignatius, 1986) he writes:

Whatever the reason, it seemed and still seems to me that that our attitude towards life can be better expressed in terms of a kind of military loyalty than in terms of criticism and approval. My acceptance of the universe is not optimism, it is more like patriotism. It is a matter of primary loyalty. The world is not a lodging-house at Brighton, which we are to leave because it is miserable. It is the fortress of our family, with a flag flying on the turret, and the more miserable it is the less we should leave it. The point is not that this world is too sad to love or too glad not to love; the point is that when you do love a thing, its gladness is a reason for loving it, and its sadness a reason for loving it more…

Let us suppose we are confronted with a desperate thing – say Pimlico. If we think what is really best for Pimlico we shall find the thread of thought leads to the throne of the mystic and the arbitrary. It is not enough for a man to disapprove of Pimlico; in that case he will merely cut his throat or move to Chelsea. Nor, certainly, is it enough for a man to approve of Pimlico; for then it will remain Pimlico, which would be awful. The only way out of it seems to be for somebody to love Pimlico; to love it with a transcendental tie and without any earthly reason. If there arose a man who loved Pimlico, then Pimlico would rise into ivory towers and golden pinnacles… If men loved Pimlico as mothers love children, arbitrarily, because it is theirs, Pimlico in a year or two might be fairer than Florence. Some readers will say that this is mere fantasy. I answer that this is the actual historyof mankind. This, as a fact, is how cities did grow great. Go back to the darkest roots of civilization and you will find them knotted round some sacred stone or encircling some sacred well. People first paid honour to a spot and afterwards gained glory for it. Men did not love Rome because she was great. She was great because they had loved her.

Misplaced Humility

Published February 21, 2009 G.K. Chesterton Leave a CommentTags: Christian, dogma, G. K. Chesterton, Humility, Orthodoxy

I am reading through Orthodoxy a second time – and yes, it is even better the second go round – and one of the points that Chesterton makes is that of humility being put in exactly the wrong place.

But what we suffer from to-day is humility in the wrong place. Modesty has moved from the organ of ambition. Modesty has settled upon the organ of conviction; where it was never meant to be. A man was meant to be doubtful about himself, but undoubting about the truth; this has been exactly reversed.

The chapter title from which I am quoting is aptly named “The Suicide of Thought”. In the preceding chapter Chesterton expresses his dismay at the popular exhortation that “you will do well if you believe in yourself”. Ha! I have always cringed at this exhortation myself. For the life of me, I don’t even know what it means. To believe is to have faith. I know how to have faith in God or even (to a certain extent) faith in others; but I have no idea how to have faith in myself. As Chesterton so wonderfully says,

Shall I tell you where the men are who believe most in themselves? For I can tell you. I know of men who believe in themselves more colossally than Napoleon or Caesar. I know where flames the fixed star of certainty and success. I can guide you to the thrones of the Supermen. The men who really believe in themselves are all in lunatic asylums.

It is exactly this conviction in one’s own abilities that Chesterton is referring to when he says that humility is in the wrong place. Instead of being a bit unsure of our own abilities, we are extremely unsure of our own beliefs. We have “opinions” and “points of view”, but never a conviction; and it is here that dogmas cease and religion (not to mention mankind) is weakened at its core. Without conviction the Creed becomes an embarrassment. There is nothing quite so pathetic as “it is my opinion that God became man for us men and for our salvation.” You might as well be honest and say, “it might be true that God became man, I’m really not sure.” To which the candid atheist might reply, “then you admit that you might be delusional.” Chesterton could not put it better when he says,

At any street corner we may meet a man who utters the frantic and blasphemous statement that he may be wrong. Every day one comes across somebody who says that of course his view may not be the right one. Of course his view must be the right one, or it is not his view. We are on the road to producing a race of men too mentally modest to believe in the multiplication table. We are in danger of seeing philosophers who doubt the law of gravity as being a mere fancy of their own. Scoffers of old time were too proud to be convinced; but these are too humble to be convinced. The meek do inherit the earth; but the modern skeptics are too meek even to claim their inheritance.

Take that post-modernist scum!

The Many Wonders of the World

Published February 15, 2009 G.K. Chesterton Leave a CommentTags: Fairy Tales, G. K. Chesterton, Wonder, Wonders of the World

One of G. K. Chesterton’s most enduring themes is that of wonder. I have noted this before, but it seems to me that Chesterton’s articulation of wonder is one of his greatest gifts to us of a more modern and mechanical age. Along with fairy-tales, Chesterton often uses children as examples of what true wonder looks like. Of course, in the end, fairy-tales and children go hand in hand, for fairy-tales are written for the amusement of children; but this is precisely what Chesterton takes issue with. Fairy-tales ought not to astonish and amuse only children. They ought to astonish and amuse us all. Our world is a very strange place, if we only have the eyes to see. The only reason we think our world is mundane is because we are so used to it. Just think of the many wonders in creation: the eternal procession of Orion through the winter night sky, the fire lilies blooming in triumphant praise during late summer, the hordes of prison striped zebras escaping into the freedom of the African plains, the wild haired cat lurking about in my living room; all of which could come out of any fairytale if they were not the stuff of the “real world”.

One of G. K. Chesterton’s most enduring themes is that of wonder. I have noted this before, but it seems to me that Chesterton’s articulation of wonder is one of his greatest gifts to us of a more modern and mechanical age. Along with fairy-tales, Chesterton often uses children as examples of what true wonder looks like. Of course, in the end, fairy-tales and children go hand in hand, for fairy-tales are written for the amusement of children; but this is precisely what Chesterton takes issue with. Fairy-tales ought not to astonish and amuse only children. They ought to astonish and amuse us all. Our world is a very strange place, if we only have the eyes to see. The only reason we think our world is mundane is because we are so used to it. Just think of the many wonders in creation: the eternal procession of Orion through the winter night sky, the fire lilies blooming in triumphant praise during late summer, the hordes of prison striped zebras escaping into the freedom of the African plains, the wild haired cat lurking about in my living room; all of which could come out of any fairytale if they were not the stuff of the “real world”.

Chesterton writes about this childlike wonder in Heretics (The Collected Works of GKC, Vol 1, Ignatius, 1986):

The child is, indeed, in these, and many other matters, the best guide. And in nothing is the child so righteously childlike, in nothing does he exhibit more accurately the sounder order of simplicity, than in the fact that he sees everything with a simple pleasure, even the complex things. The false type of naturalness harps always on the distinction between the natural and the artificial. The higher kind of naturalness ignores that distinction. To the child the tree and the lamp-post are as natural and as artificial as each other; or rather, neither of them are natural but both supernatural. For both are splendid and unexplained. The flower with which God crowns the one, and the flame with which Sam the lamplighter crowns the other, are equally of the gold of fairy-tales. In the middle of the wildest fields the most rustic child is, ten to one, playing at steam-engines. And the only spiritual or philosophical objection to steam-engines is not that men pay for them or work at them, or make them very ugly, or even that men are killed by them; but merely that men do not play at them. The evil is that the childish poetry of clock-work does not remain. The wrong is not that engines are too much admired, but that they are not admired enough. The sin is not that engines are mechanical, but that men are mechanical.

Classic Chesterton

Published February 1, 2009 G.K. Chesterton 1 CommentTags: Bernard Sahw, G. K. Chesterton, Heretics

Oh, this is good. If you enjoy Chesterton’s style of writing and thinking, you will love Heretics. If you don’t, even in the least, it would be hell to read even a page. What follows in classic Chesterton. This is why I have a smile on my face every time I read Chesterton, and why I cannot go very long without reading something of his. I realize I quote Chesterton a lot, but I have given up apologizing for that long ago.

He [Bernard Shaw] has even been infected to some extent with the primary intellectual weakness of his new master, Nietzsche, the strange notion that the greater and stronger a man was the more he would despise other things. The greater and stronger a man is the more he would be inclined to prostrate himself before a periwinkle. That Mr. Shaw keeps a lifted head and a contemptuous face before the colossal panorama of empires and civilizations, this does not in itself convince one that he sees things as they are. I should be most effectively convinced that he did if I found him staring with religious astonishment at his own feet. “What are those two beautiful and industrious beings,” I can imagine him murmuring to himself, “whom I see everywhere, serving me I know not why? What fairy godmother bade them come trotting out of elfland when I was born? What god of the borderland, what barbaric god of legs, must I propitiate with fire and wine, lest they run away with me?”

Your Philosophy Does Matter

Published February 1, 2009 G.K. Chesterton , Philosophy Leave a CommentTags: cosmology, G. K. Chesterton, Heretics, Orthodoxy, Philosophy

The following are some of the most entertaining words I have read yet by G. K. Chesterton. They come from the opening pages of Heretics, a book which I am very tardy in reading. With his typical wit and lucidity, Chesterton highlights the changing definitions of “heresy” and “orthodoxy”, as well as our modern disdain for philosophies that explain everything. “We will have no generalizations,” says GKC.

What follows comes from the opening three paragraphs of Heretics (Ignatius, GKC Collected Works Vol 1, 1986).

Nothing more strangely indicates an enormous and silent evil of modern society than the extraordinary use which is made nowadays of the word “orthodox”. In former days the heretic was proud of not being a heretic. It was the kingdoms of the world and the police and the judges who were the heretics. He was orthodox. He had no pride in having rebelled against them; they had rebelled against him. The armies with their cruel security, the kings with their cold faces, the decorous process of the State, the reasonable process of law – all these like sheep had one astray. The man was proud of being orthodox, was proud of being right. If he stood alone in a howling wilderness he was more than a man; he was a church. He was the centre of the universe; it was round him that the stars swung. All the tortures torn out of forgotten hells could not make him admit that he was heretical. But a few modern phrases have made him boast of it. He says, with a conscious laugh, “I suppose I am very heretical,” and looks round for applause. The word “heresy” not only means no longer being wrong; it practically means being clear-headed and courageous. The word “orthodoxy” not only no longer means being right; it practically means being wrong. All this can mean one thing, and one thing only. It means that people care less for whether they are philosophically right. For obviously a man ought to confess himself crazy before he confess himself heretical. The Bohemian, with a red tie, ought to pique himself on his orthodoxy. The dynamiter, laying a bomb, ought to feel that, whatever else he is, at least he is orthodox.

It is foolish, generally speaking, for a philosopher to set fire to another philosopher in Smithfield Market because they do not agree in their theory of the universe. That was done very frequently in the last decadence of the Middle Ages, and it failed all together in its object. But there is one thing that is infinitely more absurd and unpractical than burning a man for his philosophy. That is the habit of saying that his philosophy does not matter, and this is done universally in the twentieth century, in the decadence of the the great revolutionary period. General theories are everywhere contemned; the doctrine of the Rights of Man is dismissed with the doctrine of the Fall of Man. Atheism itself is too theological for us to-day. Revolution itself is too much of a system; liberty itself is too much of a restraint. We will have no generalizations…

Examples are scarcely needed of this total levity on the subject of cosmic philosophy. Examples are scarcely needed to show that, whatever else we think of as affecting practical affairs, we do not think that it matters whether a man is a pessimist or an optimist, a Cartesian or Hegelian, a materialist or a spiritualist. Let me, however, take a random instance. At any innocent tea-table we may easily hear a man say, “Life is not worth living.” We regard it as we regard the statement that it is a fine day; nobody thinks that it can possibly have any serious effect on the man or on the world. And yet if that utterance were really believed, the world would stand on its head. Murderers would be given medals for saving men from life; fireman would be denounced for keeping men from death; poisons would be used as medicines; doctors would be called in when people were well; the Royal Humane Society would be rooted out like a horde of assassins. Yet we never speculate as to whether the conversational pessimist will strengthen or disorganize society; for we are convinced that theories do not matter.

The Problem With Birth Control

Published January 25, 2009 Ethics , G.K. Chesterton 10 CommentsTags: Birth Control, Catholic, Catholic Church, Contraception, eugenics, G. K. Chesterton, Sex

Because I think controversial topics are often the things most worth talking about, I offer this reflection. It should come as no surprise that reading G. K. Chesterton has sparked what follows. In one of his essays contained in The Well and the Shallows (Ignatius 2006), Chesterton puts forth three reasons why he “despises” birth-control. His first reason takes issue with the term itself.

Because I think controversial topics are often the things most worth talking about, I offer this reflection. It should come as no surprise that reading G. K. Chesterton has sparked what follows. In one of his essays contained in The Well and the Shallows (Ignatius 2006), Chesterton puts forth three reasons why he “despises” birth-control. His first reason takes issue with the term itself.

I despise Birth-Control first because it is a weak and wobbly and cowardly word. It is also an entirely meaningless word; and is used so as to curry favour even with those who would at first recoil from its real meaning. The proceeding these quack doctors recommend does not control any birth. It only makes sure that there shall never be any birth to control.

Chesterton believes “Birth-Prevention” would be the far more honest term to use. Of course, he is right. And here we come to one of the objections to the Catholic Church’s position on birth-control in particular and contraception in general. Why is it that the Church allows for the prevention of birth via approved means, commonly known as “natural family planning”, while condemning the exact same result (birth prevention) through other means, such as the pill? On the surface this is a perfectly legitimate question and one that should be dealt with squarely. However, I am afraid that in the end this question is guilty of a blurring of distinctions between the two methods in question. As the dictum goes: distinctions! distinctions! distinctions! We must mind our distinctions!

The Catholic Church is not against the prevention of birth per se. There may be very legitimate reasons why a couple may put off having a child. These reasons are primarily between that couple and God (and possibly a spiritual director), and as such the Church cannot (and does not) make a blanket judgment in these matters. We are only to be “open to life”, but this does not entail that every sexual act is to produce a child. It is well known that the Church distinguishes between the two aspects of sexual intercourse: the unitive between husband and wife, and the life giving which produces a child. These two aspects are to always be respected, but the former may be present without the latter, assuming a legitimate reason ascertained (hopefully) through serious prayer and competent spiritual direction.

So again the question remains: why is one method of birth prevention permitted and the other is not? To put the matter simply, the answer lies in the fact that one method is in accordance with nature (i.e. the natural law) while the other is not. One method requires communication and respect between partners, the other does not. Preventing birth through natural means requires the couple to practice the virtue of temperance and restraint during the fertile periods, which requires the aforementioned communication and respect between the husband and wife. Preventing birth through unnatural means (i.e. the pill) requires no such virtue. In fact, evidence is mounting that birth control has lead to the practice of vice. A husband may look upon his wife as a sexual object who can satisfy his animal-like urges upon command. Restraint is not necessary. A young man may now have sex with a young lady and no longer fear the consequence of a child. The result is that sex is no longer sacred. It is free in the commercial sense of the word, and being free, it is cheap.

The preceding may be unconvincing to many, but, in my experience, most have not even begun to engage the arguments put forth by the Church. At any rate, the necessary distinctions are drawn and must be dealt with squarely, as the Catholic must squarely deal with the question first proposed. For a Christian – Catholic, Protestant or otherwise – the reasoning of the Catholic Church must be taken very seriously. Christians are a people of life, and as such we must be continually open to life. But if we find it necessary to delay the birth of a child, God has given us natural means to do so. What grounds do we have to reject these means in favor of other means that so easily lead to vice?

Chesterton’s second problem with birth-control is that it is a cowardly, dishonest, and ineffective form of Eugenics; and we must remember that birth control came out of the eugenics movement. His thoughts on this matter are worth quoting in full.

Second, I despise Birth-Control because it is a weak and wobbly and cowardly thing. It is not even a step along the muddy road they call Eugenics; it is a flat refusal to take the first and most obvious step along the road of Eugenics. Once grant that their philosophy is right, and their course of action is obvious; and they dare not take it; they dare not even declare it. If there is no authority in things which Christendom has called moral, because their origins were mystical, then they are clearly free to ignore all difference between animals and men; and treat men as we treat animals. They need not palter with the stale and timid compromise and convention called Birth-Control. Nobody applies it to the cat. The obvious course for Eugenics is to act toward babies as they act toward kittens. Let all the babies be born; and then let us drown those we do not like. I cannot see any objection to it; except the moral or mystical sort of objection that we advance against Birth-Prevention. And that would be real and even reasonable Eugenics; for we could then select the best, or at least the healthiest, and sacrifice what are called the unfit. By the weak compromise of Birth-Prevention, we are very probably sacrificing the fit and only producing the unfit. The births we prevent may be the births of the best and most beautiful children; those we allow, the weakest or worst. Indeed, it is probable; for the habit discourages the early parentage of young and vigorous people; and lets them put off the experience to later years, mostly from mercenary motives. Until I see a real pioneer and progressive leader coming out with a good, bold, scientific programme for drowning babies, I will not join the movement.

This brings us to Chesterton’s third problem with birth-control: those mercenary motives. The reasons for putting off children are usually selfish in nature: we want to have enough money to travel; we want our freedom to enjoy each other; we want to finish college, etc. It is with these reasons that Chesterton says his “contempt boils over into bad behaviour”.

What makes me want to walk over such people like doormats is that they use the word “free”. By every act of that sort they chain themselves to the most servile and mechanical system yet tolerated by men…

Now a child is the very sign and sacrament of personal freedom. He is a fresh free will added to the wills of the world; he is something that his parents have freely chosen to produce and which they freely agree to protect. They can feel that any amusement he gives (which is often considerable) really comes from him and from them, and from nobody else. He has been born without the intervention of any master or lord. He is a creation and a contribution; he is their own creative contribution to creation. He is also a much more beautiful, wonderful, amusing and astonishing thing than any of the stale stories or jingling jazz tunes turned out by the machines. When men no longer feel that he is so, they have lost the appreciation of primary things, and therfore all sense of proportion about the world. People who prefer the mechanical pleasures, to such a miracle, are jaded and enslaved. They are preferring the very dregs of life to the first fountains of life.

It is for these reasons, among others, that I, along with Chesterton, think the Catholic Church is wholly correct in her stance toward the modern notion of birth-control. Others are free to disagree, but one should not do so based on contemporary trends of public opinion. If you are following the sheep, you ought to discern who is your shepherd. And certainly one should not disagree and dissent for selfish motives. If one wishes to contend with the Church’s notion of the beauty of life and the sexual act, he or she should do so reasonably while engaging the arguments put forth by the Church.

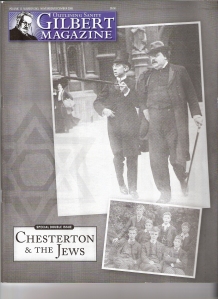

Chesterton & The Jews (Part II)

Published December 19, 2008 G.K. Chesterton 4 CommentsTags: anti-Semitism, Chesterton, Jews

Continuing on from my previous post in defense of Chesterton…

So what about the double-standard of which I spoke earlier? It is well known in our culture that there is a double-standard when it comes to the treatment of minority groups vs. the majority. Thus, in America prejudice against whites and Christians is generally tolerated, while prejudice against minority races (e.g. blacks and Hispanics) and minority religions (e.g. Hinduism and Judaism) is – rightly – cut down with a righteous indignation.

So what about the double-standard of which I spoke earlier? It is well known in our culture that there is a double-standard when it comes to the treatment of minority groups vs. the majority. Thus, in America prejudice against whites and Christians is generally tolerated, while prejudice against minority races (e.g. blacks and Hispanics) and minority religions (e.g. Hinduism and Judaism) is – rightly – cut down with a righteous indignation.

Perhaps, this double-standard is understandable, but that does not make it right. And certainly Chesterton was far too honest and good natured to play along. Dale Ahlquist credits this aspect of misunderstanding Chesterton to people not being able to recognize a joke.

Those who accuse Chesterton of anti-Semitism often overlook his enormous humor. He did not take himself seriously and in his lightness, his playfulness, his charitableness and good nature, he could point out human foibles and the sublime silliness of his fellow man without condemnation. If he stereotyped the Jews in some of his generalizations, it was because he had a great gift for generalization which was not limited to the Jews. He did the same thing with Cockneys, Irish, Germans, Americans, Moslems, Mormons, Puritans, Prohibitionists, Parliamentarians, Vegetarians, Christian Scientists, Quakers, and all the rest of us who march comically along in the grand human parade. He did not single out Jews when he made fun of their noses or their love of money, but neither did he spare them, because he did not spare anyone else, especially himself. What we love we can laugh at with impunity, which is why a husband and wife can laugh at each other, because, as Chesterton said, they both know they are fools. We need to laugh at ourselves when we are silly (instead of being offended) and we need to repent when we are wrong (instead of rationalizing or defending ourselves).

Right on. As Ahlquist said elsewhere in a different essay, “it seems that the only people who are obsessed with Chesterton’s views on the Jews are those who haven’t bothered to read him. This goes to a point I made in Part I of this blog entry. For those who have read Chesterton, even a fair amount, they will know that this charge of anti-Semitism is very out of place with what else we know about him (and what others, those he knew, said about him).

Speaking of those who knew Chesterton, it turns out that Chesterton was a good friend to many Jews. Now, the “I’m not racist, I have ______ (black, Jewish, Latino, etc.) friends” defense seems rather tired and rather lame. But if it is, in fact, true it is a perfectly legitimate defense. It’s hard to imagine a person who is actually racist against blacks being a good friend with a black guy. Try to imagine a skin-head, card carrying member of the KKK being friends with a black person. It just ain’t going to happen. So when someone is accused of such bigoted feelings, but then it turns out they have good friends that represent the object of the supposed bigotry, the accusation is undercut at the knees.

Chesterton is, famously, an alumnus of the renowned St. Paul’s School in London. The school’s famous graduates include John Milton and Edmond Halley. While at St. Paul’s Chesterton was very involved in the Junior Debating Club. It was in this club that Chesterton befriended several members, many of which became life long friends, and several of which happened to be Jewish. Quoting Ahlquist once again,

And it is significant that fully one-third of the dozen members of the Junior Debating Club were Jewish. The two sets of brothers – Maurice and Lawrence Solomon, and Waldo and Digby D’Avigdor – would not have belonged to the club had it not been for the insistence of that raging anti-Semite, G.K. Chesterton…

Lawrence Solomon (1876-1940) became one of Chesterton’s closest friends. He was a professor of history at the University of London, but when Chesterton moved to Beaconsfield, Lawrence left London and bought a home in Beaconsfield so that he could be close to Chesterton.

Waldo D’Avigdor (1877-1947) became an executive at a large life insurance company. Chesterton dedicated The Innocence of Father Brown to Waldo and his wife, Mildred.

Ahlquist goes on to comment on Chesterton’s relationship with Maurice Solomon and Digby D’Avigdor as well, but I don’t need to go on. You get the idea. Chesterton was not the bigot he is portrayed to be – or he was incredibly coy about his true feelings around his Jewish friends. Not to mention these friends would have to have been wholly unaware of the obvious bigotry that was coming from the pen of Chesterton. Something just doesn’t add up. Either those who accuse Chesterton of anti-Semitism have no idea what they are talking about, and never knew Chesterton personally, or the charge is bogus. I think the evidence I’ve outlined above (and gratefully stolen from the ACS) speaks for itself.

In yet another essay by Dale Ahlquist, he gets into more specifics on the three passages that are “almost always used in the case against Chesterton”. Perhaps, if I find some time I will do a Part III and get into the real refutation of what Ahlquist calls, the “mean and wretched lie” that Chesterton was an anti-Semite.

Of course, it goes without saying that I am enjoying my first issue of Gilbert Magazine. I’ve always enjoyed the work of the ACS, and I heartily recommend joining them in their honorable mission. You can do so at their website, http://chesterton.org/. Click the “Join!” tab at the top.

Chesterton & The Jews (Part I)

Published December 19, 2008 G.K. Chesterton 4 CommentsTags: anti-Semitism, Chesterton, Jews

Well, I went and did it. After years of donating to the American Chesterton Society (ACS), I finally joined as a member. I figure the only thing better than charitable donations is charitable donations with benefits; a 20% discount on merchandise at the ACS website and a subscription to Gilbert Magazine, in this case. Yes, I know. A little quid pro quo in your charitable giving is not exactly the Christian ideal, but let’s not quibble about theological distinctions.

Well, I went and did it. After years of donating to the American Chesterton Society (ACS), I finally joined as a member. I figure the only thing better than charitable donations is charitable donations with benefits; a 20% discount on merchandise at the ACS website and a subscription to Gilbert Magazine, in this case. Yes, I know. A little quid pro quo in your charitable giving is not exactly the Christian ideal, but let’s not quibble about theological distinctions.

As stated above, one of the benefits of joining the ACS is a subscription to their (somewhat) bi-monthly publication, Gilbert Magazine. I was happy to see that my first issue arrived in the mail yesterday, just in time before I head back to North Carolina to spend Christmas with my family. The issue’s title instantly grabbed my attention: “Chesterton & The Jews.” I have heard echos of the charge before, that Chesterton was an “anti-Semite.” I must admit, it’s a charge I’ve always had a hard time believing. Given Chesterton’s good nature, and the fact that he was so greatly loved by his intellectual antagonists, it is hard to see how Chesterton could act so “out of character” toward this one group of people. Nonetheless, all things are possible with human nature, so I was anxious to read the ACS defense of the amiable G.K. Chesterton.

One of the first articles in the magazine is an essay – or rather, a compilation essay – by Chesterton himself wherein he defends himself against the charge of anti-Semitism. But Chesterton is quick to point out that the term “anti-Semitism” is itself misleading – “a feeble and frightened euphemism.” When someone is accused of being an anti-Semite, they are really being accused of hating Jews. Semites are not necessarily Jews, in that a Semite is (according to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary) “a member of any of a number of peoples of ancient southwestern Asia including the Akkadians, Phoenicians, Hebrews, and Arabs.” So the very term anti-Semite is a euphemism, as Chesterton rightly points out. He goes on:

One of the ninety-nine reasons for not calling oneself an Anti-Semite is that it is so wretchedly polite and apologetic a thing to be. A man implies that he dislikes the Semite race, he dares not admit that he dislikes the Jewish people… There are people who dislike Jews; though I am not one of them. But I doubt if there are people who dislike Semites.

The main issue that Chesterton takes with the charge of anti-Semitism, is that it is based on a misunderstanding of what he terms “The Jewish Problem”, or worse yet, a blatant double standard of which he will have no part.

When Chesterton says “The Jewish Problem”, this sounds to modern ears a terrible bigotry. But this is only so because the term is sitting there all alone, completely out of context and without proper definition. We infer a bigoted meaning. As Dale Ahlquist (founder and president of the ACS) points out in one of his several essays, this misunderstanding is “even more complicated now because we have to try to discuss it from the opposite side of the event which is the flashpoint for all discussions of anti-Semitism: the Holocaust.” But what Chesterton meant by “The Jewish Problem” was a very real problem indeed. The Jews (prior to 1948) were a nation without a nation. So much for the problem being the mere existence of those “immoral Jews”, which is apparently what is inferred from Chesterton’s “bigoted” term.

To be more specific, “The Jewish Problem”, as Chesterton meant it, was (to quote Ahlquist again):

The “Wandering Jew” was not merely an image of literature but a fact of history. Their settlement throughout Europe was unsettled. Though they often developed a loyalty to their adopted homeland, it was different from the natural loyalty of a native. Complete assimilation was problematic for one of two reasons: Jews would either have to give up their distinctiveness, which would be unfair to Jews, or the nation assimilating the Jews would have to give up its own distinctiveness, which would be unfair and uncomfortable and probably cause resentment in that country. Chesterton said, “Jews must be free to be Jews.” In order for that to happen, he argued, they must have their own homeland, and Palestine was the logical choice.

For Chesterton, a nation was an organic unity, a people who shared the same homeland, the same culture, the same language and literature, the same religion, the same race, the same heritage, and last and least, the same government.

So “The Jewish Problem”, was in fact a real problem, and Chesterton was one of the few who was fearless enough to discuss it with all of his characteristic honesty.